Narrowing the Gates to Asylum

By Dr. Katrina Burgess and Kudrat Dutta Kontilis. (We are very grateful to Felipe Navarro for his feedback on earlier drafts.)

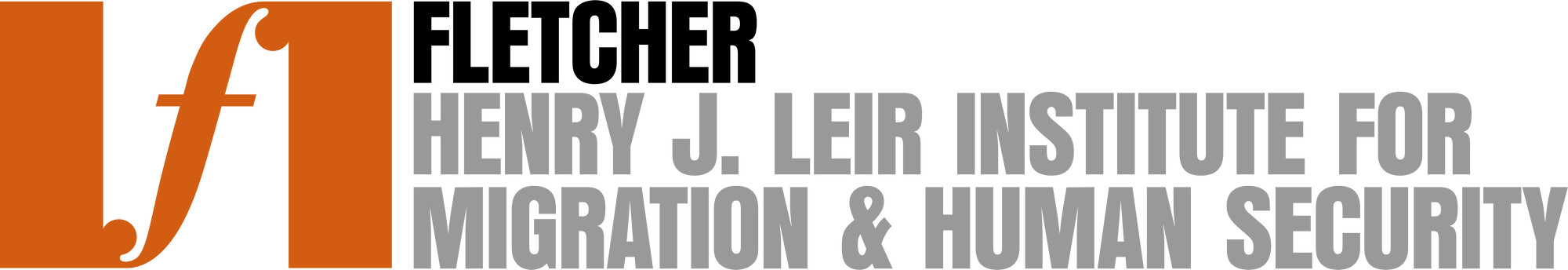

Until recently, very few migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border requested asylum, and the U.S. asylum system received little public fanfare or attention. This has changed dramatically in the past decade, putting unprecedented stress on the U.S. immigration court system (see Figure 1). As of May 2024, the immigration courts faced a backlog of more than 1.3 million asylum cases, accounting for over a third of the total backlog of 3.7 million cases.

Rather than investing in the infrastructure required to meet the growing demand for protection, the U.S. government has responded by placing more obstacles in the way of asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border. This trend reached its apogee during the Trump administration, but the Biden administration has pursued similar, if somewhat more humane, measures to narrow the gates to asylum.

In this piece, we review these measures at three stages of the process: (1) requesting asylum; (2) establishing credible fear; and (3) proving a claim and being granted asylum. To get to the first stage, most asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border must make an appointment, often with long wait times, using a mobile application called CBP One. If and when they reach the second stage, they may be subjected to an expedited review that effectively diminishes their chances of reaching the third stage. Only by crossing all these hurdles – which is extremely difficult without legal representation– can they hope to be granted asylum.

Defensive Asylum and Credible Fear

Section 235(b)(1)(A) of the Immigration & Nationality Act (INA) authorizes the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to immediately remove non-citizens whom it determines to be inadmissible under Section 212(a)(6)(C) or 212(a)(7) of the INA, a process known as "expedited removal." As is common in the realm of law, however, the INA allows for exceptions. Notable among them is the provision for non-citizens in removal proceedings to express an intention to apply for asylum, which triggers a defensive asylum claim. [1]

The process that ensues is laid out in various DHS and DOJ policy documents, which include regulations, guidelines, and memoranda with instructions on how the INA is to be implemented by DHS officers and immigration judges.[2] It starts when a non-citizen without authorization to enter the United States expresses an intention to request asylum or a fear of returning to their country at a U.S. port of entry or after being apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol. They are then referred to an asylum officer for a Credible Fear Interview (CFI).[3]

Prior to the CFI, U.S. authorities must provide the applicant with (1) an orientation to the credible fear process; (2) a list of free or low-cost legal service providers; (3) a pre-CFI waiting period of at least 24 hours after arrival at a detention site; and (4) the opportunity to waive the 24-hour waiting period. At the CFI, the asylum officer must determine whether there is a "significant possibility" that the non-citizen has been persecuted or has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of five protected characteristics: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion, or whether they would be subjected to torture.[4]

If a non-citizen passes the CFI, they may apply for asylum, withholding of removal, and/or protection under the Convention Against Torture (CAT).[5]In most cases, they are issued a ‘Notice to Appear’ with the proper Immigration Court, where they can present their case and receive a determination. Until their case is adjudicated, they are protected from removal. If they fail the CFI, they can request a determination by an immigration judge (IJ). If such a review is not requested, or the IJ affirms the negative credible fear determination, then U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) may remove them from U.S. soil.

Asylum Restrictions under Biden Administration

Despite its initial commitment to dismantle the policies adopted by the Trump administration, the Biden administration retained or reinvented many of the restrictions placed on access to U.S. asylum.

The most significant was Title 42, a rarely used section of the U.S. Code (dating to 1944) that empowers the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to bar foreigners from entering the country to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. Citing the Covid-19 pandemic – but over the objections of senior CDC medical experts, who argued that the rule had no scientific basis as a public health measure – the Trump administration invoked Title 42 in March 2020 to close ports of entry to asylum seekers and expel undocumented migrants crossing the border immediately and without any legal process.

While exempting some vulnerable groups (e.g., unaccompanied minors), the Biden administration retained Title 42 for migrants subject to removal to Mexico or their home country.[6] The result was nearly three million expulsions between March 2020 and May 2023, including of asylum seekers who had no chance to request protection.[7] Biden tried to end Title 42 in May 2022 but was blocked by a federal court until May 2023, when he formally declared the COVID-19 public health emergency to be over.

Title 42's demise did not mean a return to pre-Trump policies, however. Instead, the Biden administration placed new limits on asylum, most notably (1) an Asylum Processing Rule in May 2022; (2) a Circumvention of Lawful Pathways Rule in May 2023; and (3) a Securing the Border Rule in June 2024.[8] Taken together, these rules restrict access to asylum and leave thousands of asylum seekers stranded in Mexico in unsafe conditions or deported back home where their lives may be at risk.

Asylum Processing Rule (APR)

In anticipation of the end of Title 42, the Departments of Justice (DOJ) and Homeland Security (DHS) released an interim final rule in May 2022 to shorten asylum processing times and shift deliberations away from the U.S.-Mexico border for defensive asylum claims.

Known as the Asylum Processing Rule (APR), the measure allows asylum seekers who demonstrate a credible fear of persecution to have their cases initially reviewed by the USCIS Asylum Office, with referrals to immigration court only if asylum is not granted.[9] Previously, such cases went directly to the more adversarial and resource-intensive immigration court proceedings. The APR also restored the lower (pre-Trump) legal standard for establishing credible fear and reestablished the practice of not screening for mandatory bars to asylum at the CFI stage.[10]

Prior to adoption of the APR, a non-citizen who passed the CFI while in expedited removal proceedings was required to file an asylum application (Form I-589) within one year of their entry per 8 U.S.C. § 1158(a)(2)(B). The APR allows DHS to bypass this step for eligible non-citizens by treating the CFI as the asylum application instead of requiring Form I-589.

An asylum seeker placed in this process must be scheduled for an Asylum Merits Interview (AMI) within 21- 45 days. The AMI is conducted by an asylum officer based in a city designated by the U.S. Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) rather than at the border. This same asylum officer – rather than an IJ – determines whether or not asylum should be granted.[11]

If asylum is denied, the asylum seeker is placed in “streamlined removal proceedings” before an Immigration Court in the same city. The Immigration Court is then supposed to resolve the case within 2-4 months but may rely on the record already created by USCIS.[12] Any appeals arising out of streamlined removal proceedings are adjudicated by the Board of Immigration Appeals, the highest administrative body for interpreting and applying U.S. immigration laws.

While the APR aims for a more efficient and humane process, its implementation has been hindered by measures that prioritize expedience over protection.

- First, it raises the stakes of the CFI interview, which under current rules is conducted by phone within a few hours of an individual's arrival at a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) detention facility.[13] Attorneys are barred from entering these facilities, leaving migrants on their own to tell difficult stories to a disembodied voice in a hostile environment.

- Second, it grants DHS the discretion to shorten the time between the CFI and the asylum hearing, giving asylum seekers only a few weeks to find legal counsel and prepare their asylum case despite having to meet a higher standard of proof than the CFI.[14]

Moreover, the APR continues to rely on IJ determinations when USCIS denies asylum (which, as noted below, is in the vast majority of cases) and does nothing to address the pending claims that account for the immigration court backlog.

Preliminary statistics reveal the negative impact of APR on asylum seekers. According to an Asylum Processing Rules Cohort Report published by DHS in August 2024, 41 percent of the AMI cohort processed between June 2022 and April 2023 failed their CFI, compared to 31 percent of all cases decided by USCIS in 2022.[15] Likewise, the DHS report shows that only 25 percent of the AMI cohort who passed their CFI and moved on to an AMI between June 2022 and March 2024 were granted asylum by USCIS, compared to 48 percent of those who received a decision from an IJ in FY2023.[16]

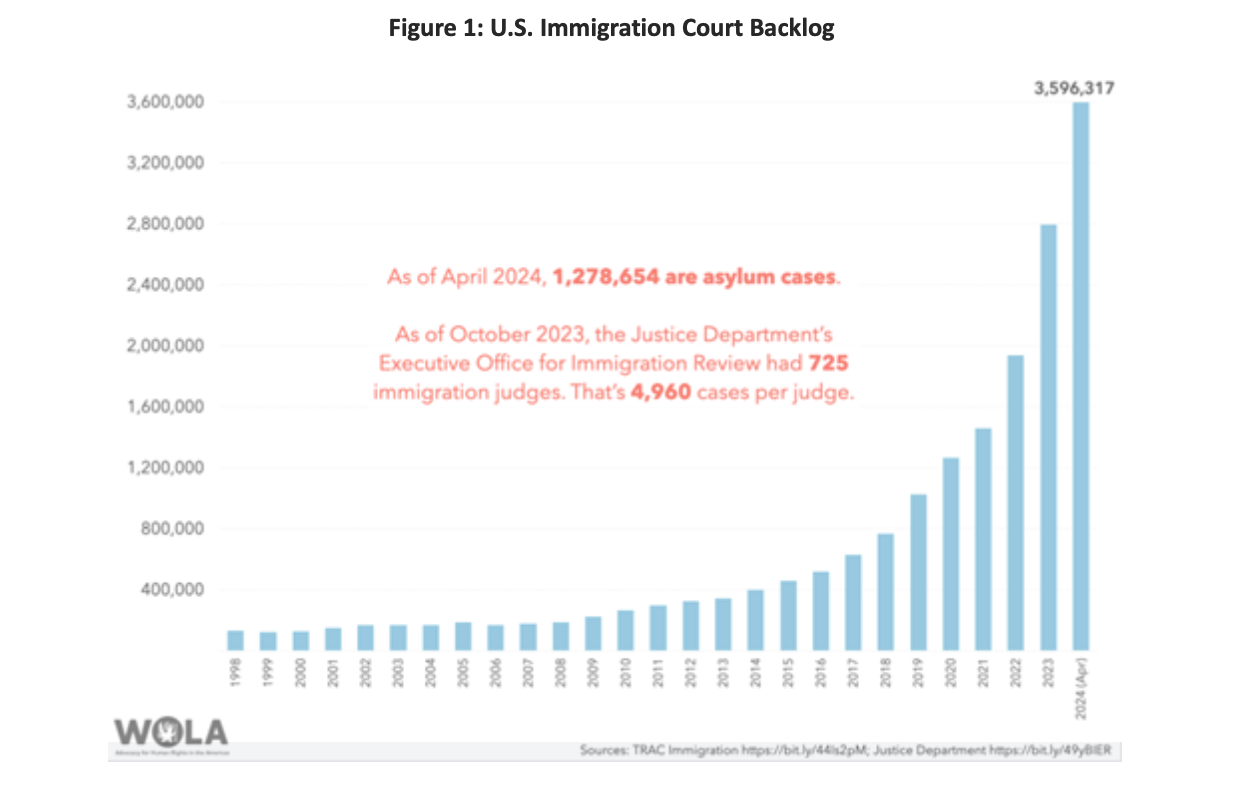

The negative impacts are even more striking when we look at legal representation. As of April 2023, only one percent of the AMI cohort had legal representation during their CFI, a rate that increased to five percent for the asylum interview and 36 percent for those referred to EOIR. Even the latter is much lower than the 87 percent who had legal representation in asylum cases decided by an IJ in FY2023. As shown in Figure 2, the implications of this gap are significant. In FY2023, the asylum approval rate for those with representation was 52 percent compared to only 21 percent for those without it.

*Source: TRAC Immigration, Two-Thirds of Court Asylum Applicants Found Legally Entitled to Remain

*Source: TRAC Immigration, Two-Thirds of Court Asylum Applicants Found Legally Entitled to Remain

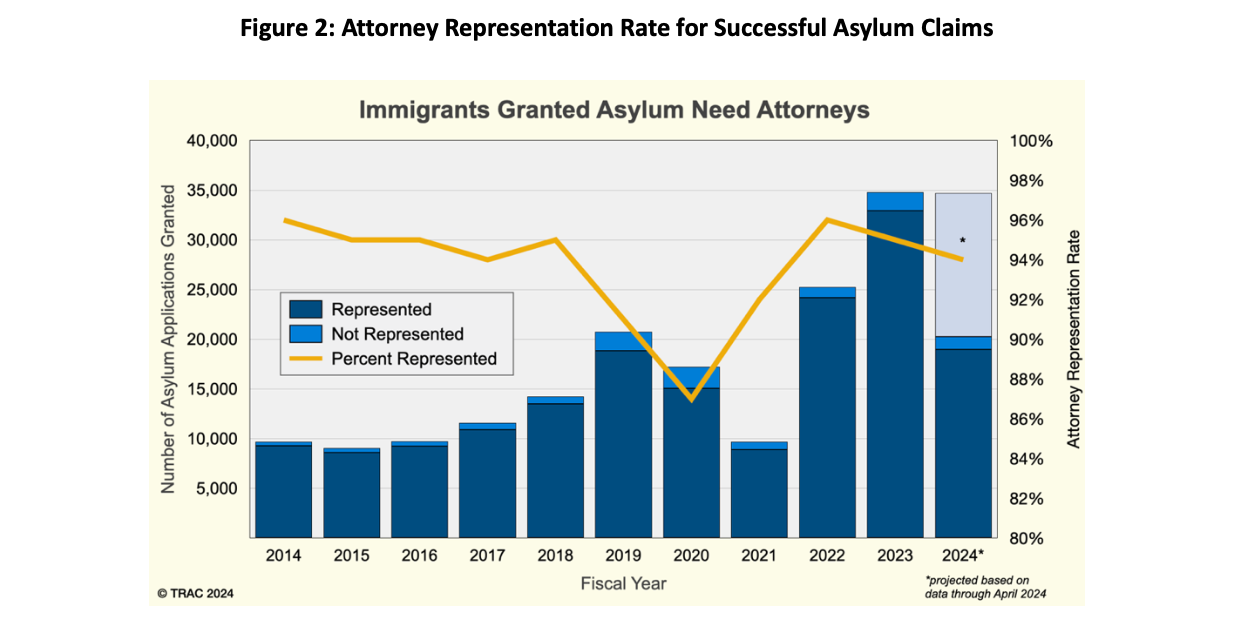

Finally, the APR perpetuates – although appears not to worsen – a trend of increased removal orders amidst falling rates of legal representation among those denied asylum (see Figure 3). In FY2023, 35 percent of all migrants in deportation proceedings were subjected to removal or voluntary departure compared to 31 percent of the AMI cohort (as of March 2024).[17] Of the former, only 22 percent had legal representation compared to 28 percent of the AMI cohort (as of March 2023). While the AMI cohort fared slightly better, it represents less than 10 percent of all asylum claims and appears to have been largely superseded by Biden's subsequent restrictions on asylum. In FY2024, the overall rate of legal representation among asylum seekers in deportation proceedings with orders of removal or voluntary departure fell further to 16 percent.

*Source: TRAC Immigration, Top Places With the Most Immigrants Recently Ordered Deported

*Source: TRAC Immigration, Top Places With the Most Immigrants Recently Ordered Deported

Circumvention of Lawful Pathways (CLP) Rule

In May 2023, the Biden administration the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways Rule (CLP). With limited exceptions, the CLP establishes a rebuttable presumption that non-citizens who cross the southwest land border or adjacent coastal borders without authorization and after traveling through another country are ineligible for asylum unless they have:

- Availed themselves of an existing lawful process (e.g., humanitarian parole);

- Presented at a port of entry at a pre-scheduled time using CBP One; or

- Been denied asylum in a third country through which they traveled.

Individuals who fail to rebut the asylum presumption remain eligible for other protections, namely "withholding of removal" and CAT, but with a higher legal standard and no path to citizenship. The CLP is currently on appeal in the 9th Circuit Court but remains in effect while the case is being adjudicated.

By blocking other pathways to seeking asylum, the CLP transformed CBP One into the primary access point for asylum seekers. Launched by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) in October 2020, CBP One was not initially intended to be a tool for collecting personal information or scheduling appointments. Starting in May 2021, NGO staff were allowed to use CBP One on behalf of migrants seeking exemptions to Title 42, but it was not until January 2023 that the app was made available to individuals seeking appointments to request asylum (or other forms of protection). Just a few months later, this option became a requirement for thousands of asylum seekers. According to CBP, more than 636,600 individuals scheduled appointments using CBP One to present at ports of entry from January 2023 through May 2024.[18]

On its face, CBP One provides a more fair and orderly system for metering asylum seekers than the previous system of requiring them to put their name on lists managed by a hodgepodge of actors on the Mexican side of the border.[19]

In practice, however, it violates a 2021 court ruling against metering and creates new barriers by excluding individuals who lack access to mobile devices or the internet, do not speak one of the three languages required to use the application, and/or have physical traits (e.g., dark skin, disabilities) that inhibit the application’s functionality.

Moreover, because only a limited number of appointments are available each day, asylum seekers often spend months waiting for their appointment while stranded in Mexico with inadequate housing and in danger of being kidnapped or otherwise victimized. By requiring the use of CBP One and thereby removing other avenues for requesting asylum, the CLP blocks many asylum seekers who may otherwise be eligible.

Despite the lower odds of gaining asylum by turning themselves into the Border Patrol after entering the country in between ports of entry (POEs), migrants continued to do so even after the CPL took effect. While smugglers often encouraged this practice, the aforementioned obstacles to getting a CBP One appointment were almost entirely to blame.

Securing the Border Rule

On June 4, 2024, President Biden issued a Proclamation and Interim Final Rule on Securing the Border under sections 212(f) and 215(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. These executive actions empower U.S. authorities to immediately and categorically suspend the right of non-citizens who unlawfully cross the U.S.-Mexico border to request asylum when the weekly average of migrant encounters between POEs reaches 2,500 per day. Once triggered, this restriction remains in effect until two weeks after the weekly average of daily encounters falls below 1,500.[20]

The Securing the Border Rule (SBR) also increases the likelihood that migrants with credible claims of fear will be deported.

- First, DHS officers are no longer required to ask them whether they fear persecution or torture, requiring instead that they spontaneously "manifest" such fear.

- Second, it gives them as little as 4 hours to find a lawyer to challenge the suspension of their right to request asylum.[21]

- Third, it sets a new higher legal standard of "reasonable probability" for the preliminary screening for other forms of protection (e.g., CAT).

Because encounters averaged 4,000 per day when the rule was issued, the restriction kicked in immediately, and U.S. authorities began subjecting migrants caught between POEs to expedited removal without the option to request asylum.

Thus far, the SBR has coincided with a drop in migrant encounters by the Border Patrol between ports of entry, which in turn has eased the immigration court backlog. According to figures released by DHS in August 2024, migrant encounters were down 55 percent and, in July, reached the lowest monthly total since September 2020. Daily border apprehensions even dipped below the 1,500 threshold a few times, although they must remain at that level for two weeks for the rule to be suspended. Meanwhile, DHS returned more than 92,000 migrants to more than 130 countries, contributing to the highest number of removals and returns in any fiscal year since 2010, and the number of new immigration court cases fell by 29% in June compared to May.

The SBR's enforcement effect remains unclear, however. Apprehensions were already declining prior to its adoption, and encounters with unaccompanied minors, who are exempt from the rule, continued to fall during June. Much of this decline can be attributed to ramped-up enforcement by the Mexican government, which detained nearly 500,000 migrants in the first five months of 2024, a pace that is unprecedented and may prove unsustainable. In addition, some experts believe that migrants are taking a "wait-and-see" approach before deciding how best to enter the United States.

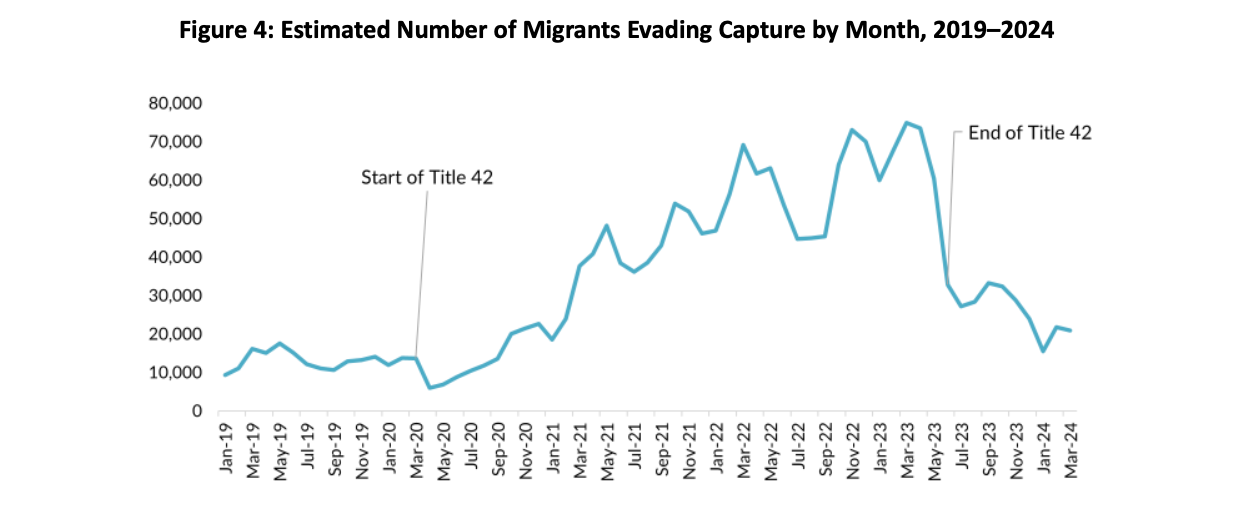

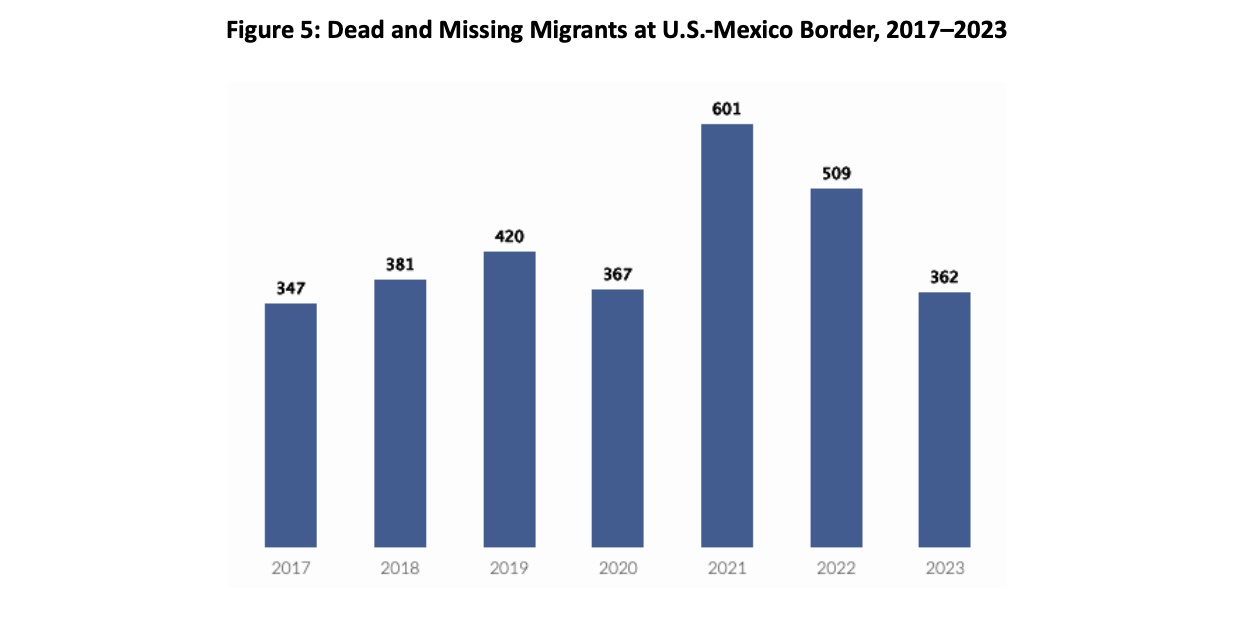

If access to CBP One does not improve, more migrants are likely to resort to crossing with a smuggler and evading the Border Patrol rather than turning themselves in to request asylum. While this option may keep encounter numbers down – because the Border Patrol's job of finding and apprehending migrants becomes more difficult – it contravenes the goal of reducing unauthorized entries and exposes migrants to an even greater risk of dying in the desert.[22]

*Source: MPI, Migration Information Source

*Source: MPI, Migration Information Source

In fact, this is exactly what happened under Title 42. Figure 4 shows that the number of migrants who crossed without being intercepted soared under Title 42 but then fell when more regular pathways were restored. Likewise, Figure 5 shows that the number of migrant deaths and disappearances spiked in 2021 and 2022 before falling back to a still deadly but more normal level in 2023. While such swings may be less dramatic under the SBR because migrants have the option to use CBP One, a similar pattern can be expected to emerge.

*Source: IOM, Missing Migrants Project

*Source: IOM, Missing Migrants Project

The SBR's effect on the immigration court backlog may be more robust but at the cost of denying protection to those who need it. Returned migrants rarely receive the paperwork they need to request asylum through CBP One and regularly report that the Border Patrol denied them any opportunity to manifest fear. Moreover, migrants from nearby countries, especially Mexico, have borne the brunt of this policy – independently of the relative merit of their asylum claims – because of the logistical challenges of detaining and deporting “hard to remove” nationalities.[23]

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the U.S. asylum system needs major reform, but the current approach of arbitrarily denying asylum seekers their day in court is inconsistent with due process and the country's domestic and international obligations.

A more humane and effective approach would be to increase the legal pathways for migrants who don't have an urgent need for protection while investing more heavily in the immigration court system for those who do. Together with more proactive and collaborative mechanisms for managing the ebb and flow of border arrivals, these measures would go a long way toward easing the pressures at the U.S.-Mexico border on a sustainable basis.

The defensive asylum process is distinct from the affirmative asylum process, which applies to individuals who have not been placed in removal proceedings because they entered the country with proper documentation (e.g., a visa), are unaccompanied minors, or were never apprehended. For more on these and other relevant terms, see the Leir Briefing Room. ↩︎

One reason asylum law is so difficult to understand is because DHS frequently changes these procedures. ↩︎

In July 2019, U.S. Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) and U.S Customs and Border Protection (CBP) signed a Memorandum of Agreement authorizing Border Patrol agents, rather than asylum officers, to conduct the CFI. The agreement was blocked by a federal judge in September 2020. ↩︎

INA § 101(a)(42)(A), 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A)(2005); Al Fara v. Gonzales, 404 F 3.d 733, 740 (3d Cir. 2005); 26 I&N Dec. 227 (BIA 2014). The Trump administration raised the CFI burden of proof from "a significant possibility" to a "reasonable possibility" but the Biden administration restored the original standard. ↩︎

DHS is obligated to inform them of this right pursuant to the Settlement Agreement in Mendez Rojas v. Wolf. No. 2:16-cv-01024-RSM (W.D. Wash. Nov. 4, 2020). It is common to apply for asylum, withholding of removal, and CAT at the same time because an applicant could still be eligible for CAT protections even if their asylum application is denied. ↩︎

Some migrants enjoyed a de facto exemption from removal under Title 42 because neither Mexico nor their country of origin would agree to receive them. As a result, Title 42 had a disproportionate impact on Mexicans and Central Americans. Venezuelans became subject to Title 42 removals to Mexico in October 2022 as part of a deal between the Mexican government and the Biden administration that also allowed up to 30,000 Venezuelans per month to request humanitarian parole in the United States. ↩︎

It should be noted that this number includes repeat attempts, which are especially frequent among single, adult males. CBP statistics show, for example, that 28 percent of individuals apprehended at the border in April 2022 had already been caught at least once in the previous six months. ↩︎

Although Title 42 continued for another year, the May 2022 rule was adopted in anticipation of its original end date before the courts intervened. ↩︎

The full name of the rule is Procedures for Credible Fear Screening and Consideration of Asylum, Withholding of Removal, and CAT Protection Claims by Asylum Officers. ↩︎

In May 2024, the Biden administration issued a Notice of Proposed Rule-Making that would allow asylum officers to screen for certain bars at the CFI stage. While the final rule has yet to be published, this proposal indicates a willingness by the administration to revert to the Trump-era procedure. ↩︎

Prior to this rule, all defensive asylum claims were decided by an IJ within the EOIR. The APR thus relocates the authority to adjudicate these claims from the Department of Justice (DOJ) to DHS. ↩︎

“The Asylum Procedure Rule”, OOD DM 22-08, Department of Homeland Security, August 26, 2022, (https://www.justice.gov/media/1248066/dl?inline). ↩︎

For a critique of this practice, see the Joint Letter to the Biden Administration to Stop Conducting Credible Fear Interviews in CBP Custody issued by 112 organizations in June 2023. ↩︎

The shortened time frame also renders them ineligible for work authorization, which makes hiring a lawyer even more difficult. ↩︎

The overall rate of CFI failure is even lower (23 percent) when including cases subject to IJ review. Between January 2021 and March 2023, 10,000 migrants who failed their CFI were found to have met the credible fear standard upon review. These individuals then joined the Court’s backlog as they awaited their regular deportation proceedings. ↩︎

This rate fell slightly to 47 percent in FY2024 but is very consistent with the historical rate of 45 percent (since 2001). ↩︎

The removal/voluntary departure rate for the AMI cohort was calculated as a share of the combined total of those granted asylum by USCIS and those referred to EOIR for removal proceedings. The removal rate for those referred to EOIR was much higher at 55 percent. ↩︎

It should be noted that some of the appointments were to request parole rather than asylum. ↩︎

The CLP’s requirement that asylum seekers request appointments through CBP One was not universally enforced, however. Some POEs continued to use parallel mechanisms for metering asylum requests such as the pre-Covid system of compiling paper waiting lists. ↩︎

Lawful permanent residents, unaccompanied children, victims of a severe form of trafficking, and other non-citizens with a valid visa or other lawful permission to enter the United States are exempted from the SBR. ↩︎

According to the New York Times, this new policy was laid out in an email from John Lafferty, the head of asylum at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, to Border Patrol officers. ↩︎

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), over 1,500 migrants have died or gone missing while crossing the U.S.-Mexico border since the Biden administration took office in January 2021. ↩︎

The SBR includes an exception for “operational considerations” related to budgetary constraints and/or the government’s lack of authority to deport everyone subject to the measure. ↩︎